Interview with Jun Mizutani (1/2) —“Professionalism is still lacking among Japanese players.”

There are several turning points for athletes, where they are forced to make big choices in their individual athletic lives. There are many cases the choice made at that time can often drastically change their playing careers; either entering further education or being employed? Playing either inside the native country or abroad? Playing either as an amateur or a professional? Either retiring or continuing an athletic career?

The following series of interviews focus on players at a turning point in their careers and the reasons of their decisions.

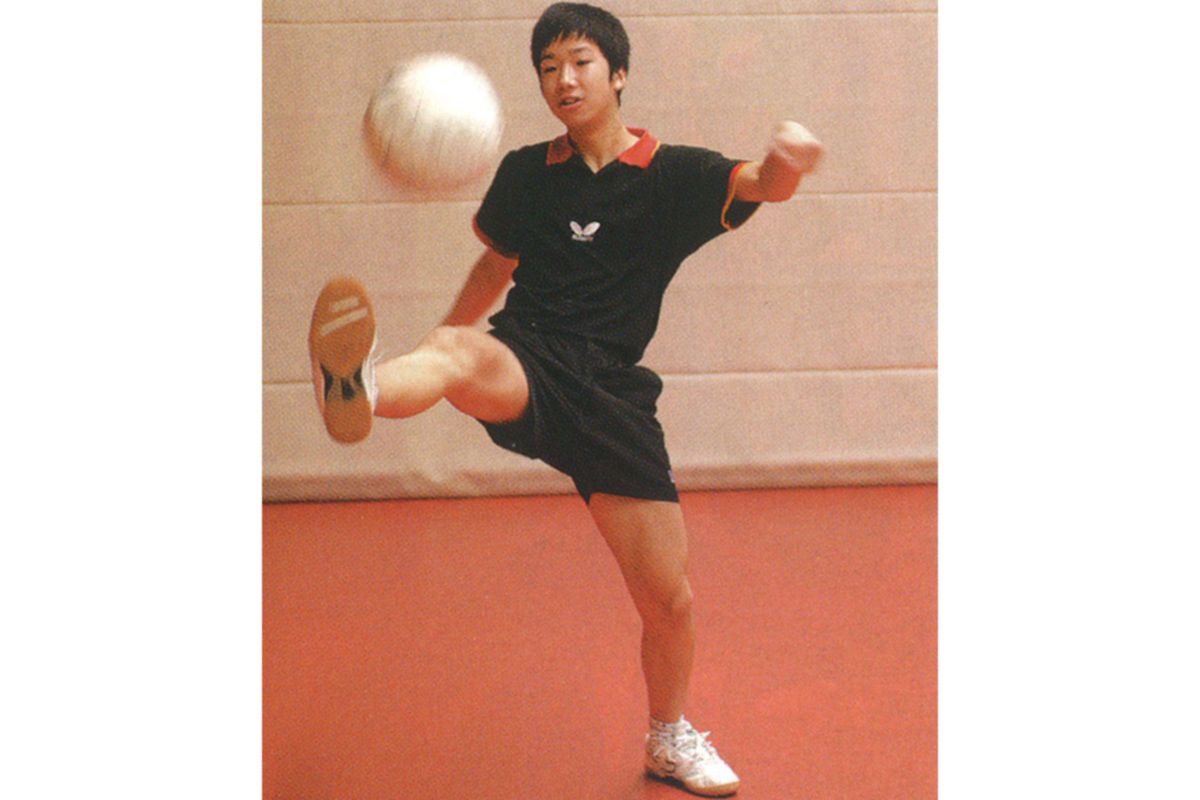

This episode features Jun Mizutani (JPN), who is now a familiar figure on TV after roughly a year from retirement. He told us about his turning points during playing days and after retirement.

— There must have been several crucial turning points during your long playing career, but what do you think was the most pivotal?

Playing in Germany and changing junior high school to Aomori Yamada. These two were vital in the sense of the biggest influences on my later life.

It was the decision to play in Germany that made me make up my mind to pursue a living playing table tennis, so I think that was my real beginning.

— What was the decisive factor of your travelling to Germany?

I remember I acted immediately, I thought it was a chance given only to me.

I would probably not have travelled to Germany if others had been granted the same opportunity and there would have been another option, but there was nobody other than me, so I decided to play in Germany without hesitation.

I was in the second year of junior high school; there were no other players with enough ability to be selected to be sent to Germany or who were mentally strong enough. No player would have been sent to Germany later if I had not decided to go there at that time.

— That said, the decision to play in Germany did not guarantee success. What was the reason why you achieved such success?

Still, I think the decision to go to Germany was the most difficult.

All I could do after arriving there was to play. I have in my memory that I enjoyed myself very much. I could practise with strong players every day; I could watch games between professionals on weekends and I could even play against very strong players. I gained a good impression that playing table tennis was fun.

— From when did you start to feel real progress?

At the All-Japan National Championships, in the same year I won the junior title, the youngest ever and reached the last 16 in the senior category; also, the youngest ever. The results were clearly the effect of half a year in Germany.

— Do you think the results were the outcome of playing in Germany?

Definitely yes. I lost in the first round of the National Championships one year before; I made it to the last 16 after playing in Germany the next year, this would not have been possible without travelling to Germany.

— What was the second biggest turning point for you?

Essentially, when I competed in different leagues, to make it short; the moments I went to the German, Chinese and Russian leagues.

— You had an awareness that you had to change something on each occasion, didn’t you?

I was eager to be stronger when I went to Germany. Mario (Amizic) was there and Mr Kishikawa (Seiya Kishikawa) and Mr Sakamoto (Ryusuke Sakamoto); they went to Germany before me; I wanted to follow their footsteps. I stayed in Germany for five years; within four years I vaguely thought I had already learnt everything from that experience.

Meanwhile, in 2008, I received an offer from the Chinese Super League; I was lucky enough to play with Ma Lin, gold medalist at the London 2012, as a teammate; I learnt a lot from him.

I think the next big turning point was in 2013, when I welcomed Mr Qiu (Qiu Jianxin) as my private coach, concurrently with starting to play in the Russian League.

I had been in the middle of slump, the biggest doldrums for me for about a year after the London Olympic Games ... it continued until the end of my playing career. I think it was 2013 that I started to work for the completion of my career, to capture medals at the Olympics.

After joining in the Russian League, I won World Tour events, achieved some good results at the World Championships, contributed to the team in the European Champions League by winning every match and so on; I thought my level had been upgraded by playing in Russia.

— Do you think your decisions on such turning points were all “correct” in the end?

I don’t think so. Thinking about those decisions I made, maybe they were all correct, maybe they were all wrong, but that doesn’t matter honestly.

It is not the decisions themselves that matter. I sometimes think I should have faced table tennis more seriously. I also think I might have achieved better results if I had dedicated myself to table tennis more earnestly.

— When in particular do you mean?

During my university days, for example. I think there must have been more I could have done.

This is also true to the days after graduating from university. I even think I was not passionate enough at the start of my table tennis career until participating in the Russian League. In a way I thought I would become stronger only by following my teammates and listening to my coach. That was partly because I relied on people who surrounded me. I was indulgent with myself. All in all, I did not know what a professional was like.

Ultimately, I was in an easy environment in Japan; I learnt from my senior colleagues, but they focused on themselves. I was used to the indulgent situation. I thought it was right at that time, but now I think that might be the reason why the Japanese team could not win in the world.

Then, by playing in Russia, I could understand what a professional was like. I could learn the tough challenging environment; I became convinced I had been spoiled. I developed exponentially once I built up the level of professionalism.

— What is the professionalism you would not have noticed if you had stayed in Japan?

The attitude towards table tennis is different, first of all.

In Japan players regularly talk with each other about practice; they often say the practice is tiring and they wish to skip sessions. They mention they are tired; the practice is exhausting, or they do not want to play.

However, I have never heard of such negative talk in Europe; they are always serious about thinking of how to win matches. They all talk about their technique in practice, and they talk about strategies and plans for the future matches. I have an impression that Japanese players rather mainly talk about skipping and missing practices.

Therefore, as a result, they finish their practice when they complete something fixed for the day. There are some players who stay at the hall for self-imposed practices, which is just normal in Europe.

— Is that what you would not have noticed without playing abroad?

Yes. I have just talked about their attitude towards practice, but the same thing can be said regarding their meals. I have never seen any Japanese players who take care of their meals. I think I am the only one who strictly controlled the dietary lifestyle in the last fifteen years or so.

Now and in the past, they all eat their favourite foods, they all go for a meal, or if they are adults, after matches for a drink, which I think is regrettable. They could make a difference to others if they were strict about themselves.

Ultimately, the people who surround them approve such an environment, they are to be blamed. There is a tradition that senior colleagues and coaches invite their team to go for a meal after matches. I think those seniors and the somewhat spoiled players who accept the invitation are inappropriate and lack professionalism.

— Have you realised eating habits affect victory or defeat directly?

When I first went to Russia in 2013, I did not moderate my dietary lifestyle and only I drank juice and ate dessert. However, nobody around me had such diet; everybody drank only water even when they won a match. That is totally different to Japan. The day of victory is just one normal day; they drink water and prepare for the next match. That’s it.

Then gradually I became ashamed of myself and became influenced by their attitude; my performance improved greatly after I started to live a strictly controlled life. Injury decreased and my strokes gained power; everything worked positively. In addition, the fact I controlled myself strictly gave me confidence. I developed a feeling that I would not or did not want to lose against them because I had followed this policy; I think that brought me quite favourable effects.

— What in details did you care about regarding dietary lifestyle?

I think it was just how an athlete is supposed to be. Just like Cristiano Ronaldo (from football), we could cut carbohydrates, refrain from taking calorie-rich drinks, choose chicken when we eat meat, and so on.

We did not have money or time for going for a meal, so we eat meals at training camps. However, the players nowadays are rich enough and have many options, so they can eat and drink whatever they like. Looking at the posts on their social media platforms, they almost always eat and drink something good on holidays (lol). I think they should do such things after retirement, just like me.

— You took part in the Russian League in 2013, so you still had a long time until retirement; did you have any turning points during the period?

A difficult period began after some problems occurred with my eyes, in a bad way. I had thought I was full of potential until then, but honestly I became aware of my limitations. In 2018 I started to think I would not improve any more when something became wrong with my eyes, so I was only to endure after that.

I should have anticipated such trouble. I had suffered broken bones twice, so I was prepared for injuries, but I had no knowledge about eyes. I had not expected I would suffer something from which I would never recover for the rest of my life, so I deeply regretted the situation. I still wish if I could have played for a bit longer.

I was in a better condition and my performance became better, but I started to feel something wrong with my eyes before I had a chance to perform even better.

— Be that as it may, you captured gold at the Tokyo Olympic Games and closed your professional career in the best possible manner. Do you still have regrets?

Of course, yes. I played table tennis because I liked the sport; I wish if I could have played until I am forty or fifty years old.

— You mentioned in your previous interview that you hoped to take part in the All-Japan National Championships as an unknown player after retirement.

I still want to compete, of course. I sometimes think I might still be able to win against younger players when I watch them play. I have a feeling that I want to compete against them, but on the other hand, I am scared in a way. Time has passed since I retired, and I finished my career with a good image, so I don’t want to realise a rusty performance.

I had difficulties in seeing the ball, so I was scared of playing, in other words I was a bit panicked, playing table tennis in such a condition.

I am worried that I would feel stressed because I have trouble in seeing the ball even if I just play table tennis for fun.

Therefore, I did not really enjoy playing in the last part of my professional career and I even hoped to get away from table tennis as soon as possible; from 2018 to 2021 was the period I had realised something unusual with my visibility. I think my eyes withstood well, to be honest.

In the second edition following this, he shares his struggles in the world of entertainment as well as his expectation and anxiety for his junior fellows in table tennis.